Homework Review

How did you go with those 6 tasks from last week’s blog? Here are the solutions that I came up with for those tasks:

Task 1: Create a Pivot Table to summarise total sales by region and income level:

Task 2: Create a Pivot Table to filter sales data by gender and drill down into sales details for a specific product category:

Task 3: Create a Pivot Chart showing sales trends over time, with slicers for filtering by customer age group and product category:

Task 4: Create a Pivot Table to analyse sales by customer age group and region to identify top-performing age groups in each region:

Task 5: Create a Pivot Table to compare sales performance by product category and income level:

Task 6: Create a Dashboard with the information you have created to summarise this information on a Managerial level:

Introduction

Nonograms (or Hanjie) are beautiful, little (and sometimes not so little) visual logic puzzles. They were invented by 2 different people, independently, around the same time; Non Ishida (1987, a graphics editor) and Tetsuya Nishio (a Japanese puzzler). Given their creation was allocated to Non Ishida, James Dalgety named the diagram puzzles after her; ‘Nonograms’. They eventually published a book together in 1993, after the UK-based Dalgety convinced the Sunday Telegraph to publish the puzzles on a weekly basis. Also, check out that single review on that Amazon listing. From my research, James Dalgety appears to be a puzzler who was just a fan of Non Ishida.

So, what are they? They are a grid made up of ‘x’ number of squares and you create an image by colouring/shading in those squares. You determine the squares to colour by the corresponding number at the top of the columns and the side of the rows. The numbers provide hints to the number of squares that should be coloured in. If there are more than one number at the top of a column/side of a row, then this indicates there are multiple sequences of squares to be coloured in.

Examples

We can see in the top row of this first example that there are three squares that need to be coloured in. For a square that isn’t being used, the player can place an X to discern a square that can be used and one that is not. We can also see that the second row must be completely filled as it requires 5 squares to be coloured in this 5×5 puzzle.

‘Castle’, 5×5. Source: https://nonogramskatana.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/20161205_230950.png

I think you’re starting to get the idea, so just marvel in these next two images.

‘Smiley Face’, 10×10. Source: https://mesacountylibraries.org/nonogram-answer/

‘Pirat[e] Ship’, 100×78. Source: https://www.reddit.com/r/nonograms/comments/n1thm1/this_is_a_massive_100x78_nonogram_called_pirate/

I would argue that, in some ways, Nonograms are to Sudoku what Checkers is to Chess. To be fair, I don’t have enough experience with either Chess, Checkers, or Sudoku to resolutely make that claim, but it’s the best point of reference that I can make for this post. With all of this information in mind, how do we actually solve them?

Solution Techniques/Definitions

Here is a non-exhaustive list of potential solution techniques that you can use when solving these puzzles. They apply for squares 5×5, 10×10, 25×25, etc. I’ll outline these techniques and show how to implement them in the puzzle activities below.

Simple Boxes

This is essentially looking for the possible places for each block of boxes. I like to think of it as approaching the problem by finding the maximum number of potential boxes first. In a 5×5, this could be 5, 4, or 3. If it’s a 5×5 and we’re provided a 4, I can use the following logic:

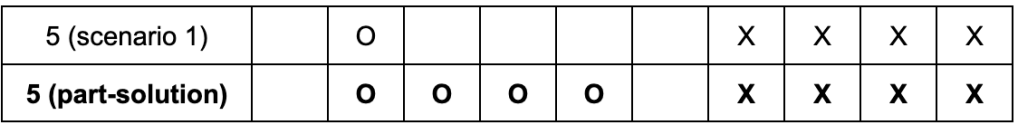

I know that in the row of 5 spaced boxes, there is the potential for 4 to be filled. So, I’ll fill 4 boxes from left to right in row 1 (scenario 1), then right to left in row 2 (scenario 2). This leaves me with 3 boxes that need to be coloured in, no matter what in the final row.

The same logic holds for larger puzzles, including a 10×10 where you have the clue 4 4 or 4 3 in a row/column.

Punctuations

Punctuating is about surrounding completed blocks with spaces to prevent errors. In a 5×5 grid, if you complete a block of 4 boxes, immediately place spaces around them. This technique often leads to additional forcing opportunities and helps maintain accuracy, especially as you scale the problems up.

Simple Spaces

This method helps identify cells that cannot possibly contain a box, making it easier to place spaces. For example, in a 5×5 grid with a clue of 2 and 1, and a box already placed in the fifth cell:

- The clue of 1 means there must be a single box somewhere, and we know that there exists a box in the fifth column cell (with an X next to it).

- For the clue of 2, you know it must include the second column as you can see from the scenarios below, 2 crosses over on the second box, regardless of counting from the left or right. The result is knowing that either boxes 1 or 3 must be a space.

Forcing

Forcing is about using existing spaces to limit where boxes can go. In a 10×10 grid (as it is easier to show this forcing technique) with a clue of 2 and 3, and punctuation in the fourth and sixth cells.

The clue of 2 is forced to the left, as it cannot fit anywhere else due to the space at cell 5. The space in cell 5 means there isn’t enough room for the clue of 2 to fit there, so it must be placed around the cells to the left. Similarly, the 3 is forced to the right due to not enough provided space in the middle portion of the row. This method helps quickly determine where clues must be placed by focusing on where they can’t go.

Glue

Glue is about using existing boxes near the edge to lock in clues. For instance, in a 10×10 grid with a clue of 5 and a box already in the second cell. The clue of 5 must include the second cell, which means it must spread across the through to the fifth cell. You can immediately fill in the third, fourth, and fifth cells because they must be part of the 5. We cannot fill either of the first or sixth cell, because we’re not sure which one can be correctly filled.

Joining and splitting

This method focuses on how boxes can either merge or split based on spacing rules. In a 15×15 grid with clues of 5, 2, and 2. If boxes are placed in cells 3 and 4, 6 and 7, 11, and 13, the first four boxes can merge into one continuous block due to the 5 clue. For the remaining 2 2 clues, we can logically say that these two boxes in cells 11 and 13 are edge cases for the two 2 patterns. This means that we can’t merge them together and we can safely punctuate a cross in the space between them; completing the 2 2 pattern.

Mercury

Mercury is a special case of Simple spaces technique. Let’s use a 10×10 grid to explain its reasoning. Let’s assume that we have 2 boxes in cells 5 and 6. We’re unsure about where the remaining two boxes are in the pattern, so we can begin to punctuate (and truncate) the row down from the edges. Placing Xs from the edges begins to limit our choices in the row. This outcome double-downs our options for the columns too, potentially increasing our changes for one of the following techniques: forcing, glueing, or joining and splitting.

Contradictions

When the other techniques have been exhausted, another approach is to use contradictions. I was formally introduced to this from a mathematical/logics perspective years ago when creating proofs; if you’re interested, have a read. You can test possible placements using this contradiction method. In a 5×5 grid, you might try placing a box in an empty cell and seeing where it leads. If placing the box leads to an impossible scenario later, you can conclude that the cell must be a space. Here’s a really nice example from the wikipedia article about Nonograms:

In this example a box is tried in the first row, which leads to a space at the beginning of that row. The space then forces a box in the first column, which glues to a block of three boxes in the fourth row. However, that is wrong because the third column does not allow any boxes there, which leads to a conclusion that the tried cell must not be a box, so it must be a space.

Mathematical Approach

Lastly, there’s also the mathematical approach where you are essentially joining multiple techniques together, including simple boxes, glueing, and joining and splitting. I’ll use two different examples to explain this.

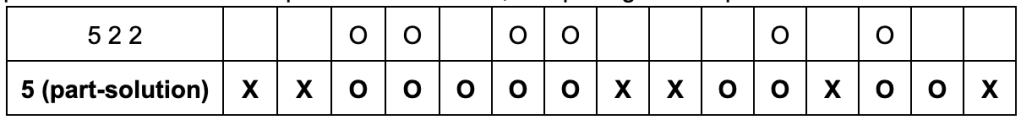

In a 10×10 puzzle, you can count the number of coloured boxes on the title (2 + 3 + 3 = 8) then add 1 for each space between the indexes (a space between 2 and 3, and a space between 3 and 3 = 2). Sum these all together and you get the total number of squares in the row (2 + 3 + 3 + 1 + 1 = 10). From this logic, we know that all of the spaces can be filled by either a colour box or punctuation.

In a 15×15 puzzle, we can use this technique to get us started. Let’s start by:

1. counting all of the coloured boxes that exist and the spaces between them; 6 + 2 + 3 + 1 + 1 = 13.

2. I’ll subtract this number from the total number of columns; 15 – 13 = 2.

3. Look for the numbers that are greater than this value in 2. (2) in the coloured boxes title. This means that we will be able to fill part of those numbers in the row.

4. Determine how many boxes can be filled by subtracting the number in 2. from those numbers:

a) 6 – 2 = 4 (boxes to be filled at this point),

b) 2 – 2 = 0 (boxes to be filled at this point), and

c) 3 – 2 = 1 (box to be filled at this point).

5. Like using simple boxes, assume that all of the boxes can be filled from one edge (left first, scenario 1; right next, scenario 2).

Activity 1 – 5×5

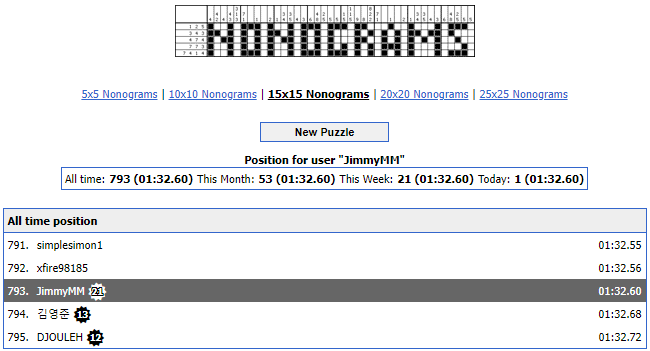

Using this website, https://www.puzzle-nonograms.com/, it randomly generates Nonograms for you of differing sizes: 5×5, 10×10, 15×15, 20×20, 25×25, Special Daily, Special Weekly, Special Monthly.

I’ve randomly drawn ID 942,912. Let’s dive into solving it:

What I will usually do is start by looking for the largest numbers in the puzzle. Since it’s a 5×5, I can immediately start with the third column which contains a 4. To determine which boxes I can colour in, I could use the simple boxes technique explained above. I’ll map 4 boxes from the top:

Then 4 boxes from the bottom:

I can look at them aligned next to one another and find the cross-over boxes:

This leaves me with the 3 boxes in the middle. (Can you already see which box we will be filling later, top or bottom?):

We can use the same approach to get column 1 started by colouring the middle block:

Since we now have two coloured boxes in the middle row, we can eliminate it by using punctuation:

Using the same logic for column 1, we can eliminate the middle column as we know that the 3 overlaps for the middle column in the top row. This means that we know the 4 starts at the top row (congrats if you had seen that after step 1):

We have 2 numbers that we need to fit in the top 2 spaces and 1 in the bottom 2. We have a 50% chance of guessing the correct space in the bottom 2, but we know that since we need to fit 2 squares into the top 2 spaces, we have a 100% chance of guessing the two spots, meaning that it cannot be anything else. If you can’t remember the term, this is called forcing:

Now that we’ve ticked off that end column, we need to fulfil the objective of 3 squares in the top 2 rows. We can now join the third and fifth columns together:

I’ll continue punctuation throughout the puzzle, making future solutions easier to see, e.g. column 4:

Since we’re crossed off column 4, we now have the visual aid of solving row 4, colouring in 3 squares. We know that the 3 cannot cross over column 4, it has to start from column 1:

You should be able to see the last few moves now, but let’s cross off the 3 in column 1 now:

Punctuate the space out in row 5, column 2:

Finish cross out column 2 all together:

Which leaves us 1 last space to colour:

Activity 2 – 10×10

Let’s start again by looking at the largest numbers first; simple boxes. We’ll start by looking at the 8s (columns 3 and 4) then move to the 7 (row 7) using the glueing technique:

I’ll now complete the 5s in rows 5 and 6, then block out the 2 in row 4 (glueing again):

I’ll apply some punctuation around the grid to find more solutions:

I can now finish off the 5 in row 1 (splitting), 4 in row 3, and punctuate the 4 in row 8:

This makes things a lot easier to see. I can remove the 2 space in row 2 (punctuation and contradiction), columns 3 and 4, completing the 8s in columns 3 and 4 (contradiction):

Next, finish off row 2 by following the logic in either row 2 or columns 6-10:

Next, the 3 in column 1 (as there are 3 spaces to fill), then punctuate the 2 in row 10 so that I can fill in the 5 spaces in column 2:

Some further punctuation can now clear up the puzzle a bit more:

We’re almost there. I’ll take care of column 10 as this 2 3 fits perfectly into the column, meaning that I can polish off rows 5-10 much quicker:

Some punctuation again:

After the final two rows, then we’re done!

Activity 3 – 15×15

See if you can pick out the tactics whilst you follow the video:

Conclusion

I hope this has helped you with your journey into Nonograms. Have you been solving them for years? Have you just found them through this post? Did this post give you some insights about them you didn’t previously know? Comment down below and let me know what you’re thinking. Hope to see you on the leaderboard!

2 responses to “66 – How to Solve Nonograms”

[…] perspective), possess a drive to correct any misunderstanding I have of something along the way, finding beauty and appreciating it for its high- or low-entropy state because it exists for its reason, and a life-long learner who […]

[…] How to solve Nonograms […]