If I asked you what the price of a pencil is today, what would you say? What if I asked you what the price of a pencil is today knowing that it was $1.05 yesterday – what is the price of the pencil today? What about if it was $1.05 two days ago and $1.05 yesterday? $1.00 three days ago.

(FYI: I had written this scenario as a bat just to use that algebra example…but where could you find a $1 bat nowadays? I’m assuming that this problem may have begun in the 1950s or something and they didn’t account for the legs on that problem and the inflation that came with it…or whoever constructed it wanted someone to start thinking about the logistics of finding a $1 bat? Or maybe, and most probably, I just started thinking too deeply into it. Tangent over.)

Let’s try this this one:

On 6th February, 2024, the close Amazon stock price (AUD) was $168.75. What price would you say it was on the 7th of February? What if you knew the stock price was $170.31 on 5th February? And $171.81 on the 2nd? $159.28 on the 1st? First thing I think of is the 2nd must have been a sunny day.

There are many different ways that you can approach these types of questions. Today, we’re going to look at two approaches: autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA). I believe that the moving average approach (method) is easier to understand than the other, so let’s start there.

Here’s the Google Sheet for this week’s post:

What is the moving average (MA)?

It is a technical analysis indicator that helps level price action by filtering out the noise from random price fluctuations. From a stock perspective, it essentially tells you the price of that stock over time and takes out the wider fluctuations over time. In MA models, the value of the time series at a particular time point is modelled as a linear combination of past forecast errors, rather than past values of the series itself.

Maths

We can observe different approaches to MA, including simple moving average (SMA), exponential moving average (EMA), and the mathematical MA model.

- Simple moving average (SMA):

SMA = (A1 + A2 + … + An)/n,

Where:

A = average in time period n,

n = Number of time periods

SMA Example

I have monthly stock data for 6 months and I was asked to calculate the 6 month SMA:

January = $30, February = $35, March = $41, April = $49, May = $53, June = $49

SMA = (30 + 35 + 41 + 49 + 53 + 49)/6 = 42.833

- Exponential moving average (EMA):

EMAt = [Vt * (s/1+d)] + EMAy * [1−(s/1+d)]

Where:

EMAt = EMA today

Vt = Value today

EMAy = EMA yesterday

s = Smoothing

d = Number of days

EMA Example

I have stock valued at $30 today and it had an EMA value of $35 yesterday. I’m going to pick a 20 day average, and a smoothing factor of 2.

EMAt = [30 * (2/1+20)] + 35 * [1−(2/1+20)] = 34.52380952

This is compared to the SMA of:

(30 + 25)/2 = 32.5

For a 20-day moving average, the multiplier would be [2/(20+1)]= 0.0952. The smoothing factor is combined with the previous EMA to arrive at the current value. The EMA thus gives a higher weighting to recent prices, while the SMA assigns an equal weighting to all values. When N (the number of periods) increases, 2/(1+N) tends to decrease, resulting in a slower reaction to new data points. This behaviour aligns with the principle that as more periods are considered in the calculation, older data points have less influence, leading to a smoother and more stable average. Conversely, when N decreases, 2/(1+N) increases, giving more weight to recent data points and making the EMA more responsive to changes in the underlying data.

Difference

Essentially (and over simplistically), the more complicated the formula, the more accurate the model is trying to replicate the movements in data points. When using the exponential moving average, compared to the simple moving average, the former response much quicker to change, as can be seen in the image below:

Source: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/movingaverage.asp

- Mathematical MA model:

Xt = μ + εt + θ1εt−1 + θ2εt−2 + … + θqεt−q

Where:

- Xt is the value of the time series at time t,

- μ is the mean of the series,

- εt is the white noise error term at time t, 1, 2, …,

- θ1, θ2, … , θq are the parameters of the model, and

- q is the order of the model.

Mathematical Model example

Consider a stock market analyst who is studying the volatility of a particular stock. In a moving average model, the analyst assumes that today’s volatility is related to the past forecast errors in predicting the stock’s performance. For example, if recent forecasts have consistently underestimated the stock’s volatility, today’s volatility might be expected to be higher. Let’s forecast it:

Mathematical Representation:

Xt = μ + εt + θ1εt−1 + θ2εt−2 + … + θqεt−q

Where:

- Xt: Today’s volatility.

- μ: The mean volatility.

- εt, εt−1, …, εt−q: Forecast errors from previous time periods.

- θ1, θ2, …, θq: Parameters representing the impact of past forecast errors on today’s volatility.

Let’s substitute some values in:

εt−1 = 1.5

εt−2 = 0.8

εt−3 = 1.0

μ = 10

θ1 = 0.5

θ2 = 0.3

θ3 = 0.2

εt = 2.5

Let’s substitute the values in:

Xt = μ + εt + θ1εt−1 + θ2εt−2 + … + θqεt−q

Xt = 10 + 2.5 + 0.5*1.5 + 0.3*0.8 + 0.2*1.0

Xt = 13.69

This model says that today’s volatility is 13.69.

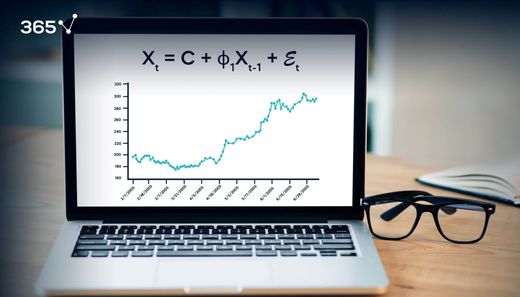

What is autoregressive (AR)?

Well, what would you say? Breaking it into its parts, we have auto- and regressive. Auto is self-referential and regressive is returning to a former or less developed state. So, ultimately, what we’re going to do is forecast future prices by looking at the prices that the object previously was. In AR models, the value of the time series at a particular time point is linearly related to its own past values, i.e., the model assumes that the current value of the time series depends linearly on its past values.

Maths

Mathematically, an AR(p) model of order p can be expressed as:

Xt = c + ϕ1Xt−1 + ϕ2Xt−2 + … + ϕpXt−p + εt

Where:

- Xt is the value of the time series at time t,

- ϕ1 , ϕ2 , … , ϕp are the parameters of the model,

- c is a constant term,

- εt is the error term assumed to be white noise (random error), and

- p is the order of the model.

Example

Suppose we are analysing the daily temperature of a city. In an autoregressive model, we assume that today’s temperature depends on the temperatures of the previous days. For instance, if the temperature has been increasing over the past few days, we might expect today’s temperature to be higher as well. Let’s forecast it:

Mathematical Representation:

Xt = c + ϕ1Xt−1 + ϕ2Xt−2 + … + ϕpXt−p + εt

Where:

- Xt: Today’s temperature.

- Xt−1, Xt−2, …, Xt−p: Temperatures of the previous p days.

- ϕ1, ϕ2, … , ϕp: Parameters representing the impact of past temperatures on today’s temperature.

- εt: Random error term.

Let’s substitute some values in:

Xt−1 = 24

Xt−2 = 22

Xt−3 = 21

ϕ1 = 0.6

ϕ2 = 0.3

ϕ3 = 0.1

c = 5

εt = 2

Let’s substitute the values in:

Xt = c + ϕ1Xt−1 + ϕ2Xt−2 + … + ϕpXt−p + εt

Xt = 5 + 0.6*24 + 0.3*22 +0.1*21 + 2

Xt = 30.1

So, this models says that the temperature today is forecasted to be 30.1 degree celsius.

You might be thinking that ‘you can’t solely rely on the moving average model or the autoregressive model. Yes, they’re important by themselves, but I know they have an impact on one another.’ You’re right. The next model we’re going to look at is the combination of these two AR and MA.

ARMA

ARMA models are used for modelling stationary time series data, where the mean, variance, and autocorrelation structure of the data do not change over time. They are commonly used in econometrics, finance, engineering, and other fields for time series forecasting, anomaly detection, and understanding the underlying dynamics of a system.

Maths

Mathematically, an ARMA(p, q) model can be expressed as:

Xt = c+ϕ1*Xt−1 + ϕ2*Xt−2 +…+ϕp*Xt−p + εt + θ1*εt−1 + θ2*εt−2 +… + θq*εt−q

Where:

- Xt is the value of the time series at time,

- c is a constant term,

- ϕ1, ϕ2, … , ϕp are the autoregressive parameters,

- εt is the white noise error term at time, and

- θ1, θ2, …, θq are the moving average parameters.

Example

Suppose we are analysing monthly sales data for a retail store over several years. We want to develop a statistical model to understand and forecast future sales based on past performance. Deciding to use an ARMA model to capture the underlying patterns in the sales data, let’s see if we can forecast these sales.

- Autoregressive Component (AR):

- We observe that the current month’s sales are likely influenced by the sales in previous months. For example, if there was a promotional event or a new product launch in the previous months, it could affect the current sales. Therefore, we incorporate an autoregressive component into our model to capture this dependency. Let’s say we include the sales data from the past 3 months (lag 1, lag 2, and lag 3) as predictors in our AR component.

- Moving Average Component (MA):

- We also notice that there may be random fluctuations or shocks affecting the sales data that are not explained by the autoregressive component alone. These could be due to factors such as changes in consumer preferences, economic conditions, or other external factors. Therefore, we include a moving average component in our model to capture these random fluctuations.

Mathematical Representation:

Monthly Salest = c + ϕ1*Monthly Salest−1 + ϕ2*Monthly Salest−2 + ϕ3*Monthly Salest−3 + εt + θ1*εt−1 + θ2*εt−2

Where:

- Monthly Salest represents the sales in the current month,

- Monthly Salest−1, Monthly Salest−2, and Monthly Salest−3 represent the sales in the previous 3 months, which constitute the autoregressive component.

- εt represents the error term at time t, capturing the random fluctuations not explained by the autoregressive component,

- εt−1 and εt−2 represent the errors in the previous two months, which constitute the moving average component, and

- c, ϕ1, ϕ2, ϕ3, θ1, θ2 are the parameters to be estimated.

Let’s substitute some values in:

Monthly Salest−1 = 1000 (sales in the previous month)

Monthly Salest−2 =1100 (sales two months ago)

Monthly Salest−3 =1050 (sales three months ago)

c = 500 (intercept or mean term of the ARMA model)

ϕ1 =0.6 (autoregressive parameter for lag 1)

ϕ2 =0.3 (autoregressive parameter for lag 2)

ϕ3 =0.1 (autoregressive parameter for lag 3)

εt =50 (error term for the current month)

θ1 =0.4 (moving average parameter for lag 1)

θ2 =0.2 (moving average parameter for lag 2)

Let’s substitute the values in:

Monthly Salest = c + ϕ1*Monthly Salest−1 + ϕ2*Monthly Salest−2 + ϕ3*Monthly Salest−3 + εt + θ1*εt−1 + θ2*εt−2

Monthly Salest = 500 + 0.6*1000 + 0.3*1100 + 0.1*1050 + 50 + 0.4*εt−1 + 0.2*εt−2

Monthly Salest = 1585 + 0.4*εt−1 + 0.2*εt−2

Now, we need the values of εt−1 and εt−2 to proceed further. These are the error terms from the previous two months, which are typically obtained from historical data or generated using a random process. Once we have the values of εt−1 and εt−2, we can plug them into the equation to find the forecasted value of Monthly Salest. There are numerous ways that we can generate these error terms:

- Random Variations:

- Generate random values for εt−1 and εt−2 using a random number generator, e.g., εt−1 = 20 and εt−2 = -15,

- Residuals from a Previous ARMA Model:

- If there is a previously available fitted ARMA model to the data and obtained residuals, this method is how the residuals εt−1 and εt−2 are fitted.

- Historical Forecast Errors:

- Use previous models forecast errors from a previous period as proxies for εt−1 and εt−2, e.g., εt−1 = 30 and εt−2 = -10,

- Seasonal Patterns:

- If the data exhibits seasonal patterns, you could use seasonally adjusted forecast errors as εt−1 and εt−2. For example, if higher sales are observed during certain months due to holidays or other seasonal factors, then the errors should adjust the forecast errors accordingly.

- Residuals from a Simple Forecasting Model:

- If a simple forecasting model has been used (e.g., a moving average or exponential smoothing model) to generate forecasts, use the residuals from that model as εt−1 and εt−2.

For this case, I will use number 1:

Monthly Salest = 1585 + 0.4*20 + 0.2*-15

Monthly Salest = 1590

So, using this ARMA(3,2) model, the predicted monthly sales will be $1,590.

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve journeyed through the use and impact of different models’ ability to forecast future values in a time series data, using the example of stock prices and monthly sales data. We explored two main approaches: the autoregressive (AR) model and the moving average (MA) model, along with their combination in the autoregressive moving average (ARMA) model.

The moving average model, with its focus on filtering out noise from random price fluctuations, provides a straightforward approach to understanding and predicting trends in data. By averaging out past data points, it offers a smoothed representation of the underlying pattern, aiding in making informed forecasts. On the other hand, the autoregressive model delves into the self-referential nature of time series data, recognizing that the current value depends on its past values. This approach captures the temporal dependencies within the data, allowing for the prediction of future values based on historical trends.

We also explored the ARMA model, which combines elements of both AR and MA models to provide a comprehensive framework for analysing time series data. By incorporating both autoregressive and moving average components, the ARMA model offers a powerful tool for capturing the underlying dynamics of a system and making accurate forecasts. Through mathematical formulations and practical examples, we demonstrated how these models can be applied to real-world scenarios, such as predicting stock prices and sales figures. By understanding the principles behind these models and their implications, analysts and researchers can gain valuable insights into the behaviour of time series data and make informed decisions.

In conclusion, the choice of model depends on the specific characteristics of the data and the objectives of the analysis. Whether it’s capturing long-term trends with the moving average model, understanding temporal dependencies with the autoregressive model, or combining both approaches with the ARMA model, these techniques offer powerful tools for forecasting and decision-making in various fields.

2 responses to “46 – Autoregressive Moving Average Models”

[…] ARMA models […]

[…] There have been more than a few instances where I have been able to utilise some of the techniques and solutions that I have developed over the past year. If you’ve been following the blog, or have checked out my resume, I have been working a few different jobs over the past year. I have been able to use some of those Excel/Google Sheets solutions, specifically in projects that involve: time scheduling (how to optimise workers around costs), implement conditional probabilities of outcomes and decisions that arise from these probabilities, develop an Excel function to provide decisions based on numerical analysis, and provide inputs to a solution that could be solved using a SARIMA model. […]