Solution from Last Week’s Problem

Given what you learned from the blog last week, were you able to solve the problem using the matrix method?

Adalia and James shopped at the same store. Adalia bought 5 kg of apples and 2 kg of bananas and paid altogether $22. James bought 4 kg of apples and 6 kg of bananas and paid altogether $33. What is the cost of 1 kg of bananas?

As a simultaneous equation, we would set up this problem as:

5x1 + 2x2 = $22 (1)

4x1 + 6x2 = $33 (2)

In matrix form, we would have:

So, we can view this equation to be:

XA = B

First, let’s take the inverse of A:

Let’s solve X by using the inverse of A:

Since we’ve arranged the X matrix to be x1 as apples and x2 as bananas, this means that 1kg of each product are each worth:

$3 for apples, and

$3.5 for bananas.

Since posting last week, I was considering what it would mean to be solving these problems within a workplace. Various departments in various organisations and businesses could use these matrix algebra techniques to assist in quickly arriving at decisions based on data-driven insights. For instance, Accounting and Finance workers can use it to calculate financial ratios, including efficiency, liquidity, and profitability. It can also be used to analyse and interpret income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statement data.

It can also be used within operations management, like solving optimisation problems through linear and integer programming; like the salesman problem. Finally, it can also be used within marketing departments. This is especially true for analysing performance of their campaigns. Matrix algebra can be used to measure effectiveness of campaigns and their impact. This information can assist companies in directing future campaigns.

Now that we understand how different workers can utilise this technique, let’s look at an example from an advertising perspective.

Advertising Example

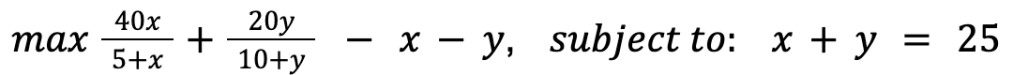

The equation below shows the total sales (S) that a business observed after spending money on two types of advertising (x and y). This relationship is summarised as:

The business discovers that the profit is 20% of the sales minus its advertising costs. The firm wants to spend only $25 on these pieces of advertisements. With these needs (and constraints) being set by the business, we can calculate profit by determining how to allocate the advertising budget between the two advertisements.

We can write the profits as:

The profit maximisation function now be rewritten as:

We are going to remove the inequalities from this problem:

For this problem, we assume that the objective function and the constraint function are defined on the open set D = (−1, ∞)2. Since ∇h(x, y) = (1, 1), the non-degenerate constraint qualification (NDCQ) is satisfied for all (x, y) in the constraint set.

NDCQ is satisfied if the rank at x* of the Jacobian matrix of the equality constraints and the binding inequality constraints is 𝑘0+𝑚.

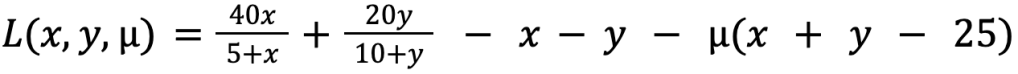

Now, we can form the Lagrangian:

Then derive the first order conditions (FOCs):

The partial derivative equations (x and y) imply that (5 + x)2 = (10 + y)2. There is also the implication that they are also equal, together, with the third equation, (5 + 25 – y)2 =(10 – y)2. Therefore, this equation only has one solution, y = 10.

We can now derive the optimal x*, y*, and μ* values, 15, 10, and -1/2 respectively, as the unique critical point of the optimisation problem.

The constraint function defined by h(x, y) = x + y is affine. For function to be affine, the domain of the problem is D dimensional, equality constraints introduce a D-1 dimensional surface limitation into the feasible region. This is a line in a two dimensional problem, a plane in a three dimensional problem and a hyperplane for higher dimensions, due to the form of the constraint h(x)=wTx+b=0. Therefore, the constraint set is convex. The objective function, π|(-1,∞)2, is concave on its domain (-1, ∞)2, and the Hessian matrix can be written as:

It is negative definite for all (x, y) such that x, y > -1. Thus, this optimisation problem is a concave program with (x*, y*, μ*) = (15, 10, -1/2) as the unique global maximum. Since (x*, y*, μ*) = (15, 10, -1/2) is also feasible (an element of the constraint set, and since the constraint set is a subset of the constraint set, (x*, y*, μ*) = (15, 10, -1/2) is also a unique solution.

Accounting Example

Two goods (Q1, Q2) are produced by a firm in competitive market the total revenue (TR) and total cost (TC) functions are shown below:

TR = 15Q1 +18Q2

TC= 2Q2 + 2Q1Q2 + 3Q22

It turns out that the two products are related to one another in production as the marginal cost of one is dependent on the output level of the other, i.e., ∂TC/∂Q1 = 4Q1 + 2Q2.

In order to maximise profits (π) for the firm, we can initiate Cramer’s rule (a) for the first-order condition and the Hessian matrix (b) for the second-order condition.

a)

The first-order conditions are

∂π/∂Q1 = π1 = 15 – 4Q1 – 2Q2 = 0

∂π/∂Q2 = π2 = 18 – 2Q1 – 6Q2 = 0

Like last week’s post, we can view this in matrix form,

Cramer’s rule tells us that:

xi = det Ai/det A,

where xi is the ith unknown variable in a series of equations, det A is the determinant of the coefficient matrix, and det Ai is the determinant of a special matrix formed from the original coefficient matrix by replacing the column of coefficients of xi with the column vector b.

Using Cramer’s rule to solve the problem, we see that:

|A| = 24 − 4 = 20

|A1| = 90 − 36 = 54

|A2| = 72 − 30 = 42

Therefore,

So, this tells us that the critical points for Q1 and Q2 are respectively 2.7 and 2.1.

Now we can use the Hessian matrix to test for second-order conditions,

where H1 = −4, and

H2 = (-6 * -4) – (-2 * -2) = 24 – 4 = 20.

The Hessian matrix is negative definite and there is a local maximum in a critical point C. Therefore, we can say that profits, π, have been maximised.

Conclusion

There are many different ways that we can utilise matrix algebra in business. The tricky parts are asking what we are trying analyse and calculate, find the necessary data, and understand how to arrange them in the matrix form. Have you been able to think of a way you can use matrix algebra in the workplace?